British-era water tank narrates the story of Padmavati & Kanchi Abhijan

This legend has been told and retold over centuries and in all forms including the world-famous Pattachitra paintings of Raghurajpur.

Padmavati

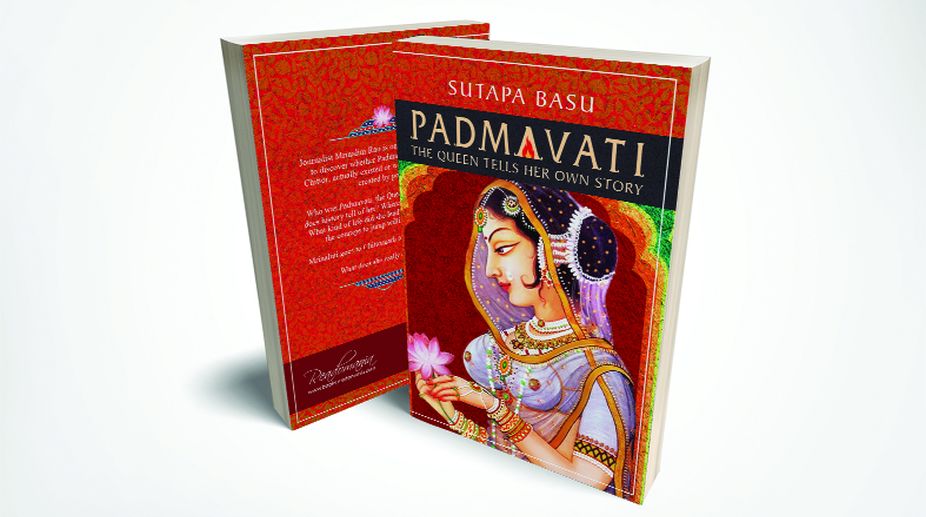

Mythological fiction having become the mainstay of Indian publishing; here comes a timely version of the 16th century legend of Padmavati, piggybacking on a roaring controversy about the film, which no longer dares to use the full name.

Once upon a time, in 1540 to be exact, Amethi-based Sufi poet Malik Mohammed Jayasi penned a story on a time-honoured theme, that of a prince, a princess and a lascivious king of another land. It was set in Rajasthan, not in Ayodhya, but it sounded a lot like the saga of Ram and Sita turned geographically upside down — the princess was from Lanka, and the evil Sultan from the northern plains of Hindustan. Jayasi’s saga unfolded not 2,000 years ago but two centuries prior to his own time, in 1306.

The broad outlines of Jayasi’s story are thus. Among the various wives of the heir apparent of Chittor there might (or might not) have been a particularly beautiful one called Padmavati. Sultan Alauddin Khalji, despite (or because of) his own harem of beauties from around the world, may have coveted her. He may have got only a glimpse of her, or may have seen paintings of her, or seen only her reflection, or been convinced by courtiers or war strategists in his own camp that here was a woman for whom it was worthwhile to lay siege to the Chittor Fort. He successfully did so in 1306, ten years before he died, but the princess and all the women in the fort committed jauhar (mass self-immolation), preventing the conquerors from consummating their lust.

Advertisement

A story with such romance and drama was bound to grab the attention of filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali. The theme of illicit love, palace intrigues, grandiose forts and royal shenanigans were already his forte, and it was natural for him to go for one more colour-coordinated costume drama to set the box office afire. He probably knew the theme would generate controversy but that usually helps in garnering publicity. However, it was a bit surreal how descendants of the Chittor royals and other upholders of public morality worked themselves into a rage without having watched a single scene from the film. Its release was inordinately delayed and is now set for 25 January.

Publishers have been quick to cash in on the controversy, which has raged for over a year. In the book under review, author Sutapa Basu offers a masterly literary work embellished with the descriptive flair she has demonstrated in earlier books. She uses the ingenious tack of a journalist going to Chittor Fort and tracking down a diary left by Padmavati herself, as suggested by the subtitle The Queen Tells Her Own Story. So from the tale in Awadhi dialect to the film in Hindi to the English version, the legend crosses all language barriers.

Although the cast of characters is broadly the same, including a talking parrot expert in spying on the enemy, Basu has taken creative liberties with the plot, just as (we presume) Bhansali did. The story of romantic love between the two royals is a bit over-the-top, considering the man already has 13 wives and Queen No 1 is bound to wreak revenge, as Lord Ram’s stepmother did aeons ago. Today, we are all aware that Shah Jahan’s love Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to his 13th child and he did not hesitate to re-marry after his grief had been buried in white marble.

What of the ingenious trick by which Khilji “saw” Padmavati and yet did not, a story told with great flourish by guides to the fort even now? This is how the writer imagines it, and perhaps Bhansali will show it,

“The royal carriage with the Sultan and the Rawal halted at Padmavati’s palace. Guards flung open the gates. Women veiled in gaudy chuneris sprinkled them with rose petals as the men entered. But the Sultan was too impatient to half for the tilak ceremony. He strode ahead, his head turning here and there seeking the beauty of his dreams. Ratan Singh ran after him and guided him up the stairs to the pavillion. There, a group of soldiers in Chittor’s livery met them. Before he could protest, they bound Alauddin’s eyes with a black cloth and guided him to a wide mirror placed high on a wall…”

Instead of revealing too much of the plot, it would be productive to discuss that mysterious entity called Indian culture, in defence of which filmmakers are physically attacked and an actor threatened with her nose being chopped off (probably the Ramayan came to mind, especially as the princess is from Lanka). Culture has layers that cannot be explored in popular cinema or literature, which relies heavily on visual aesthetics. For instance, ideal women are described as Padminis in our texts, and Jayasi goes so far as to say that the Lanka king offered no less than 16,000 of these to his son-in-law! Digging deeper, one discovers that there were four types of women according to Hindu erotology — the Padmini (lotus woman), Chitrini (arty type), Shankhini (conch shell) and Hastini (elephant woman). There are also elaborate instructions as to the days and hours in which different classes of women are to be wooed.

Before this raises feminist hackles, one must add that men too are categorised as being of three types — the Shastra (hare), Vrishabha (bull) and the Ashwa (horse). What distinguishes one type from another is the size of their linga, measured by finger-breadths; they would be of a specific build and shape, their features would be sharp or blunt, their colour dark or fair. And the man would also have a specific temperament; for example, “He is of a quiet disposition; he does good for virtue’s sake; he looks forward to making a name; he is humble in demeanour; his appetite for food is small, and he is moderate in carnal desires. Finally, there is nothing offensive in his semen.”

While all this may seem repugnant to modern-day sensibilities, Indian culture does not make this elaborate classification in order to give the less well-endowed man performance anxiety. The idea is that the right man must find the right woman, not just to satisfy his lust or for procreation, but to achieve, hand-in-hand with a partner, moksha, or release from the endless cycle of birth and re-birth. There are also four stages of moksha, but these need not detain us here, except to mention that if a man gets a Padmini, he gets a smooth merger into the godhead. That’s why he pursues her with such dedication, even at the cost of countless lives.

Khalji might have been unaware of these subtleties when he laid siege to the fort, nor would he be seeking salvation. But what about sati and jauhar, which the proponents of Rajput valour sometimes try to defend? Basu builds up the story in such a way that the reader feels that Padmavati’s act was justified. We feel empathy for the women who bravely face the flames rather than fall into the marauders’ hands. We may not be so sympathetic to the Mewar royals’ ploy of buying off the Sultan 10 chests of gold, for these days we can question the ways of the patriarchs. But it is after all a tale of a time long ago, and an eco-system so different from ours. It is neither Basu’s case nor Bhansali’s that such customs should be glorified.

The book also causes us to ruminate on the utility of forts meant to protect the privileged royals who tried to secure their lives in huge structures that themselves became death traps. In surrounding villages, life would not have been so comfortable, or secure from man or animal, but at least there would be many escape routes and chances to survive in disguise or by pretending to be of the ruler’s faith. At least women there did not have to die at their own hands, or because of a diktat from the patriarchs. One does not grudge Rajasthan its beautiful forts, which have become heritage hotels and venues for destination weddings, but one should not mourn the passing of a way of life in which mass suicide was regarded as an honourable practice.

It’s not very different, in the modern day, from a rejected young man wanting to kill or harm the object of his affection so that nobody else can have her. This, unfortunately, is also part of Indian culture.

The reviewer is the author of In Search of Ram Rajya and That’s News to Me.

Advertisement